Take our AI survey

Scientific news has partnered with Trusting News to gather feedback on the potential use of AI in journalism. Currently, we do not publish any content produced by generative AI (see our policy). We want to hear your views on how Scientific news can use AI responsibly. Tell us by taking a short 10-question survey.

Most black holes that astronomers have discovered fall into one of two categories. They are either stellar-mass black holes, up to 100 times the mass of the Sun, or supermassive black holes, which reside in the centers of galaxies and are hundreds of thousands to billions of times the mass of the Sun. the sun .

Black holes with masses in between may help bridge the gap between the two categories and explain how the supermassive ones got so big. But these black holes are a bit like Bigfoot: There have been many claimed sightings, but most turn out not to be real. (SN: 2/8/17).

“There is a fairly wide mass range, between 100 and 100,000 solar masses, where there are very few discoveries,” says astronomer Maximilian Häberle of the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Heidelberg, Germany. “It’s interesting to find out if they’re there, and we just don’t see them because they’re hard to detect. Or maybe there’s a reason why they don’t exist at all.”

One reason to think that medium-sized black holes must exist is because the supermassive black holes that astronomers have seen in the early universe did not have time to grow so large if they simply ate gas and stars as black holes do today . (SN: 1/18/21). If those black holes grew from merging intermediate-mass seeds, this could solve the puzzle (SN: 6/2/23).

“It’s like a missing link that’s needed to explain the existence of supermassive black holes,” says Texas-based astronomer and data scientist Eva Noyola, who was not involved in the new work. “If this is proven [intermediate-mass black holes] occur in dense star clusters, you have a solution that is quite elegant and simple.”

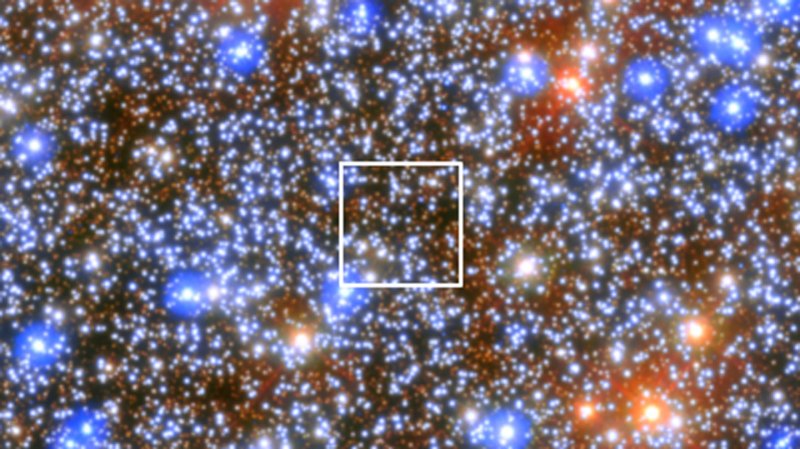

So astronomers have been hunting for medium-sized black holes for decades, and have been looking for Omega Centauri specifically since 2008. As the most massive star cluster in the Milky Way, it’s a relatively easy place to look for and can be the remnant core of another galaxy that merged with the Milky Way about 10 billion years ago (SN: 11/1/18).

“It’s basically a galactic core frozen in time,” says study co-author Nadine Neumayer, also of the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy. Its black hole may be representative of all black holes in small galaxies 10 billion years ago. “It immediately tells us something about the seed mass for black holes.”

But previous studies left it unclear whether Omega Centauri had a single medium-sized black hole, or a cluster of smaller black holes close together.

Using 20 years of Hubble Space Telescope observations, Heberle and colleagues tracked the motions of 1.4 million individual stars in the cluster and looked for stars that were moving faster than expected.

The team found seven stars swirling around the innermost regions of the cluster at speeds between 66 and 113 kilometers per second – speeds that should have ejected the stars from the cluster altogether. The only way those stars could remain in the cluster is if a single massive object holds them close, the team concluded.

Observations of the superfast star, combined with other observations over the years, should settle the debate about the black hole in Omega Centauri, says Noyola, who was on the team that first claimed to see the black hole in 2008 and was met with skepticism when they reported. Outcome.

It wasn’t until more than a decade later that astronomers caught undeniable evidence of an intermediate-mass black hole. The first solid detection came from the LIGO gravitational wave observatory, which recorded ripples in space-time as two smaller black holes merged to form a single black hole of about 142 solar masses.SN: 9/2/20). But this collision occurred about 17 billion light-years from Earth, making it difficult to study.

The Omega Centauri black hole has two advantages over it, from an astronomer’s point of view: It is in our galactic neighborhood, and astronomers can continue to observe it. Hӓberle and his colleagues are planning to use the James Webb Space Telescope, or JWST, to get more information on the speed of the rotating stars, which will allow them to put better limits on the black hole’s mass. .

Another group, led by astrophysicist Oleg Kargaltsev at George Washington University in Washington, DC, is using JWST to look for the light emitted by super-hot gas flowing into the black hole.

“It will be a completely independent, very different method of proving that an intermediate-mass black hole exists,” says Kargaltsev.

#mediummass #black #hole #spotted #time #galaxy

Image Source : www.sciencenews.org